By Bryan Runck, PhD, Senior Research Scientist, GEMS Informatics Center

While you’re working on your short game for a breezy 83-degree 4th of July golf game, the snow and cold of winter is close to our minds this summer.

Winter is Coming

Winter kill on golf course greens is a major problem for superintendents and golf courses across cold climates. It’s a hard phenomenon to study though because it happens so intermittently, so we can’t easily reproduce it in experimental settings or identify ahead of time where it will happen.

The solution: generate large data collection systems and deploy them over vast spatial extents.

Since 2019, my lab has worked with the UMN Turfgrass program to do just this. We have scaled up from 7 sensor nodes with 49 sensors in 2019 to 80 sensor nodes with over 1600 sensors for the the 2022 to 2023 winter. In the following, I’ll share a bit more on what happened this last winter and what we’re up to this summer.

Refurbishing Sensors

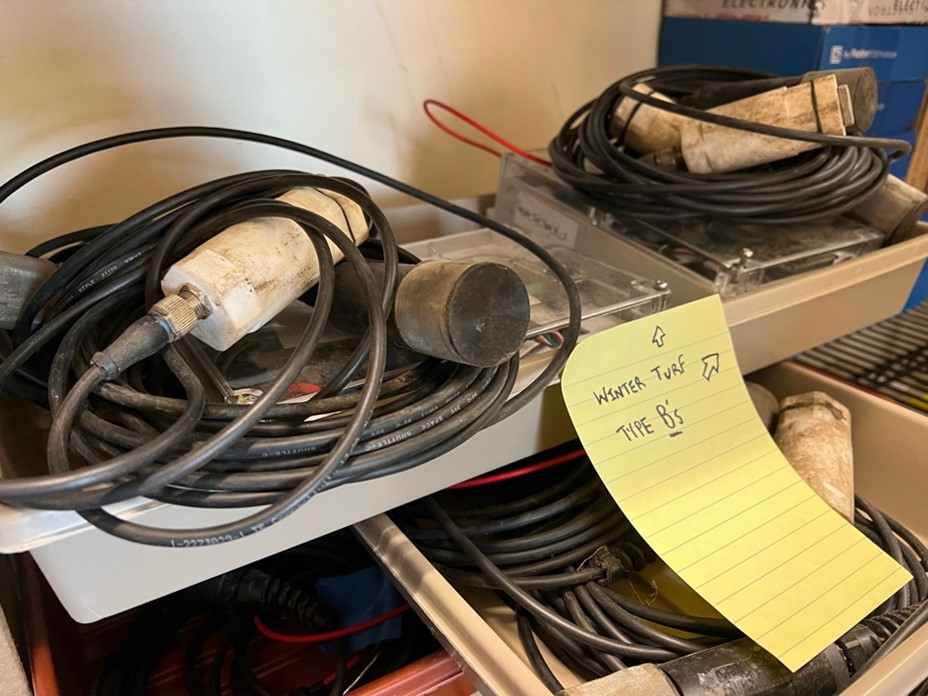

To start, we’ve gotten most of the devices used during this past winter shipped back to the University of Minnesota. Once we get these devices, we take an inventory of every box to ensure we’ve gotten everything back (Figure 1). Then, we do a physical inspection of the hardware; this includes checking each inch of cable by hand for cuts or cracks, evaluating the logger and circuitry for any corrosion, and assessing the state of each sensor to ensure its integrity (Figure 2). While we have the logger lid off, we also pull the local SD card and store that data (which we compare to the data we received on our servers). The result of this process is a list of repairs needed for each node. Repairs will be done through July and August on the nodes. This will include replacing sensors or other components that are compromised.

In addition to physical checks, we will also perform random spot checks for sensor drift across sensors. This ensure that the sensors are still performing in line with manufacturer specifications. Once these steps are complete, the sensors will be used to collect data again on golf courses this upcoming winter.

Integrating Data from Drones and Satellites

Working with U-Spatial, the Yang Lab, and the Knight Lab, we are working to integrate imagery with the sensor data and the survey data golf course managers provided. U-Spatial has architected an integrated data model that will ingest all the data. Then, we’ll provide this data back to the research team in near analysis-ready fashion in a few months or so, which will kick off the next round of analysis and modeling to understand winter kill.

What are we seeing in the data?

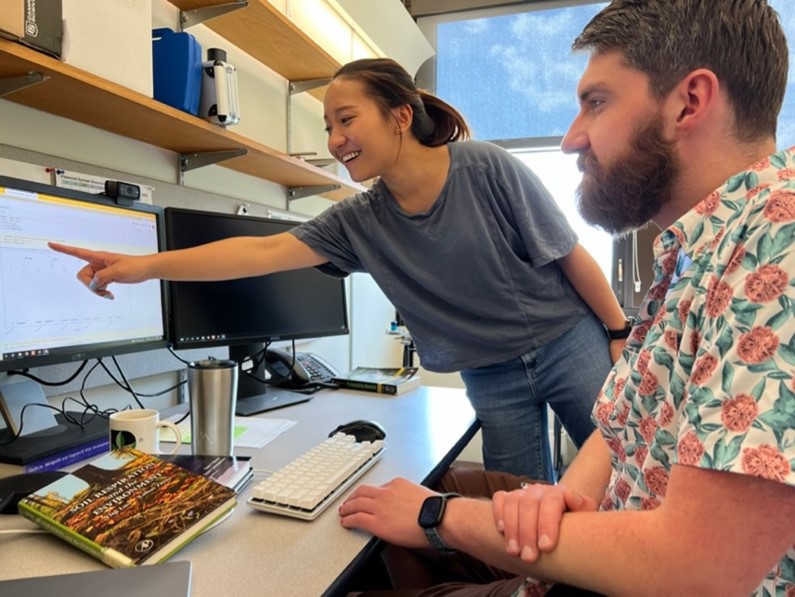

While we are still very early in the project, what we’re seeing in the data is promising, both from a system evaluation standpoint and for providing indication about what’s happening below the surface of the green (Figure 3). Of particular interest, we’re seeing negative correlations between CO2 and O2, two important gasses for understanding plant respiration, which fits expectations because plants take in CO2 and respire O2. What this ultimately means for winter kill is still unknown, but gives us a strong indication that we’re on the right track.

Funding

We’re extremely grateful for funding from the Minnesota Golf Course Superintendents Association, the United States Golf Association, and the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Institute for Food and Agriculture. None of this work would be possible without their support.